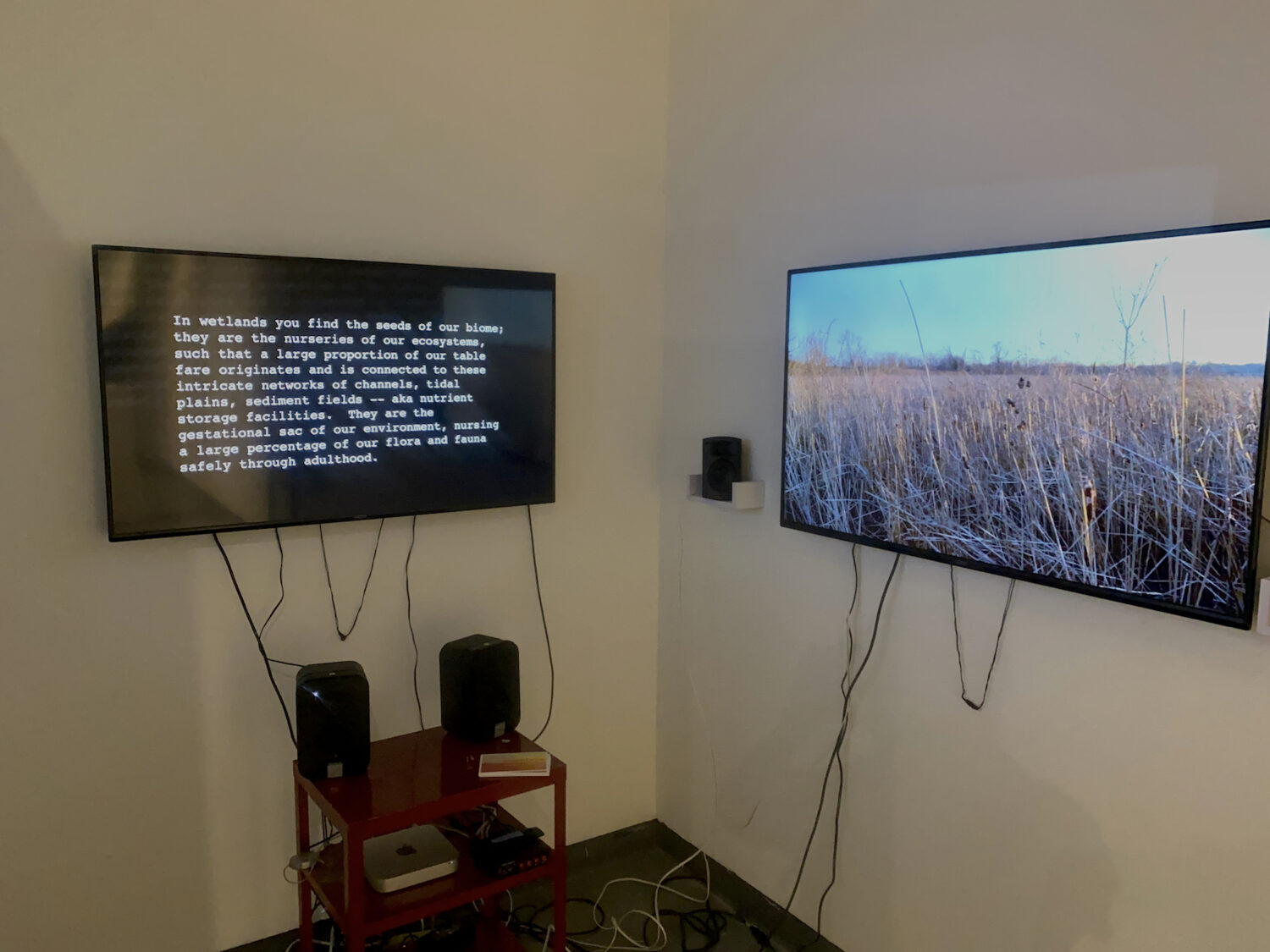

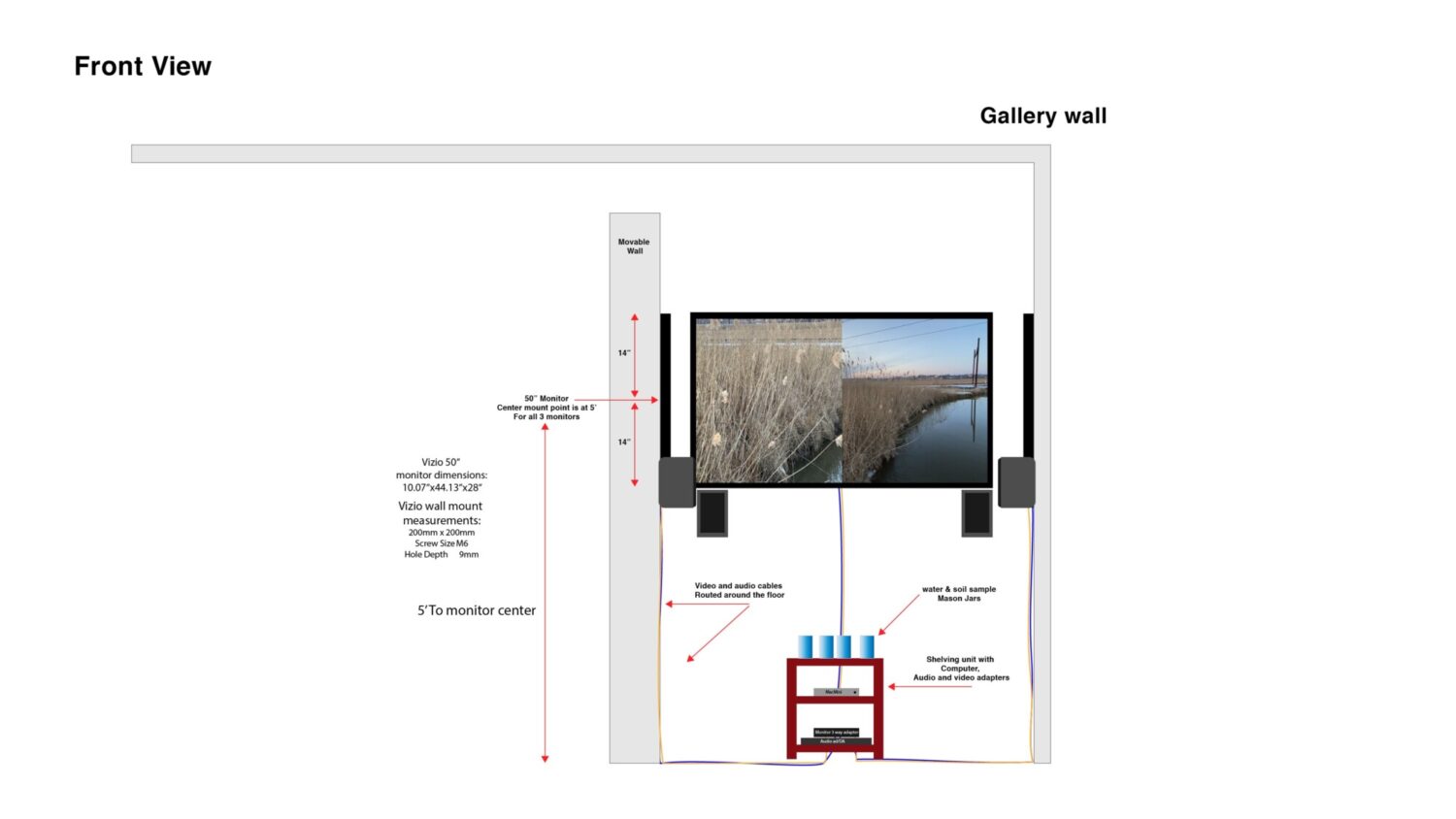

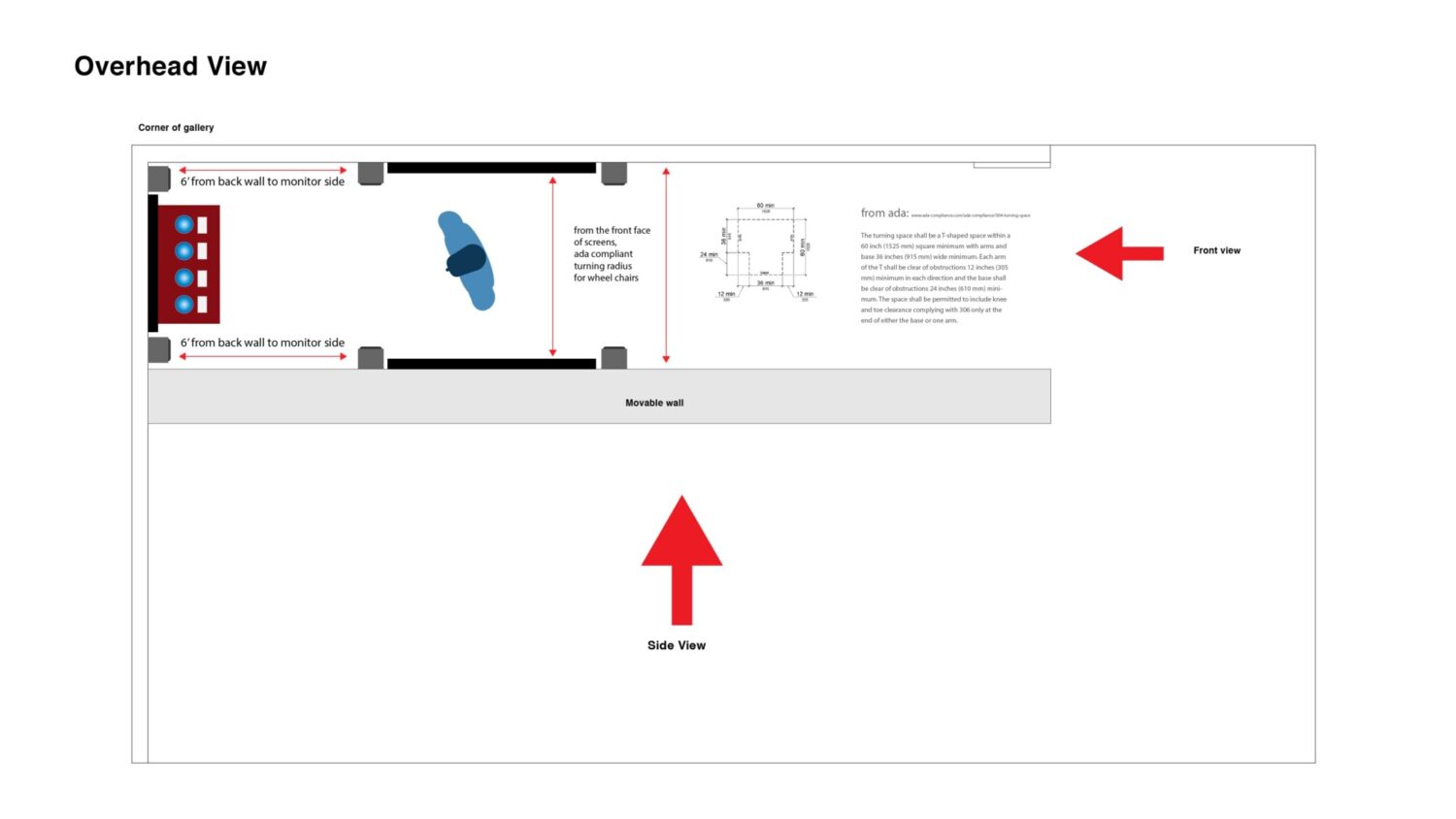

Triggered Redundancy is a three-channel video installation created from footage shot in a wetland within the Delaware Watershed. It was accompanied by sound compositions, text, and historical images, all sequenced into a semi-immersive space at the Delaware Contemporary Museum.

The project’s goals were to inform, enlighten, and highlight the historical, natural, and inspiring qualities of the marsh, allowing the audience to reflect on what these geographies mean to them.

This piece is part of my ongoing work on marshlands, water, historical and post-colonial expectations and realities, as well as the environmental costs of humanity’s follies.

Marshlands have always captivated me, whether in person or through the writings of authors like Romain Gary and Mark Twain. I have an instinctive attraction to these so-called “wastelands.”

Perhaps this connection is influenced by my Chinese zodiac sign, the Water Ox, or maybe it stems from my birthplace—an island once surrounded by salt marshes. It could also be tied to my ancestors, who came from the coasts of Guinea in Africa. Whatever the reason, I experience a complex mix of wonder, relief, and joy when I encounter these landscapes, but I also feel sadness and frustration.

Wetlands around the world are facing permanent destruction due to various human activities. Their degradation and alarming decline serve as an early warning for what could happen in the future to the rest of the natural world, particularly our coastlines. The loss of these ecosystems has a ripple effect on both marine and terrestrial macrosystems, impacting all aspects of our natural environment.

Wetlands are the seeds of our biome; they serve as nurseries for our ecosystems. A significant portion of our food comes from, and is linked to, these intricate networks of channels, tidal plains, and sediment fields—essentially nutrient storage facilities. They act as the gestational sac of our environment, nurturing a large percentage of our flora and fauna as they grow into adulthood.

Wetlands are valued spaces for many indigenous cultures and are considered a significant source of resources. Historically, these communities have carefully managed and protected these areas, but they have often been undermined by colonization and resource extraction driven by capitalism.

Wetlands have also served as crucial refuges for marginalized groups. In the Americas, they provided hiding places for runaway slaves, persecuted indigenous peoples, criminals, and indigent individuals during difficult times. Many formed maroon societies, creating hidden villages in these secluded environments.

Throughout history, armed conflicts have shown how swamps, bogs, and marshes can create challenges for conventional armies. These terrains often hinder efforts to root out revolutionaries, insurgents, and those attempting to escape.

As a young child, I remember looking out of the car window, wondering what types of creatures lurked beneath the dark green waters and reeds that seemed to be everywhere between the pylons of the Grand Central Parkway, driving away from LaGuardia Airport in New York. I also recall fishing with my dad and cousin on a bridge in Casamance, Senegal, pondering whether the catfish hiding in the marshes just out of reach were larger and more plentiful than those in the middle of the bridge. Additionally, every time I landed in Miami from various origins, I wondered if one day I could spend real time exploring all the extensive marshes surrounding the city. However, once we landed, the oppressive humidity and heat of South Florida drained all my energy and enthusiasm—despite being a Caribbean kid, I had grown up in the dry, arid Sahel, and this climate was not my friend.

But in Florida today for example, when you land in present day Miami, what you will see out of the planes portholes is an unsustainable and infinite grid of mediteranean styled subdivisions, surrounded by larged paved roads, with endless parking lots, all aligned with canals of various sizes leading to artificial retention ponds and lakes, plumes of spray released by aeration fountain jets, there to prevent the re-marshification of these tools of “land reclamation”. In my lifetime the wetlands that used to dominate south Florida are just a vestige of their past glory, and florida is a leading example of the american environmental disaster in all it’s extremes.

The wetlands of my childhood, once miraculous nurseries for native fauna and flora, have been transformed into a purgatory of parking lots, strip malls, and sprawling mega ranch homes. These developments have become leading sources of pollutants, contributing to increasingly dangerous and pervasive red tides. The irresponsible introduction of exotic plant and animal species by the residents of these subdivisions has caused an explosion of non-native species, displacing and eradicating native plants and animals. These issues are just some symptoms of Florida’s unsustainable coastal overdevelopment.

Today, when driving to many airports, you’ll notice marshlands surrounding the areas, often positioned between the intricate networks of major highway interchanges. In the Northeast, these wetlands are now dominated by dense growths of Phragmites australis, an invasive Eurasian reed that is spreading rapidly across the United States due to rising temperatures, which create ideal conditions for these warmer temperate plants.

The sediment in most wetlands on the East Coast is heavily contaminated with 500 years’ worth of historical and contemporary PFAS pollutants, heavy metals, pesticides, and artificial fertilizers. These harmful substances continuously seep into the watersheds of the streams and rivers that feed into the wetlands, where they settle and concentrate in the slow-moving waters.

Coastal wetlands across the Americas, Africa, Oceania, Europe and Asia are disappearing due to various environmental factors stemming from human actions against these often-underappreciated ecosystems. A principal cause of the rapid loss of once-abundant coastal and estuarine wetlands is climate change, particularly sea level rise. Additionally, centuries of neglect and disregard for the vital role these wetlands play in the food web have contributed to their decline.

Historically, factories and industries would frequently dump toxic sludge into these areas, fully aware that public perception would largely overlook these so-called “wastelands” or “mosquito havens.” Governments sought ways to quickly monetize these seemingly unused lands by filling them with construction waste or “reclaiming” them for industrial zones, wastewater management facilities, or airport developments.

As we urgently need the natural barrier that coastal wetlands provide to mitigate flooding during superstorms and extreme tidal events, these wetlands are increasingly threatened. A combination of rising water levels and seawater intrusion is elevating the salinity of these areas from brackish to nearly pure seawater. This shift kills off native grasses and reeds, which traditionally helped stabilize the soil. As a result, the land that supports the wetlands further dissipates, creating a vicious cycle that hinders the growth of new plants, making it even more difficult to combat sea level rise.

In these now significantly reduced areas, life continues as various creatures, both “marketable” and commercially non-valued, are still born here and subsequently move up the food chain through different life cycles.

Marshes provide habitat for prey fish such as killifishes, mummichogs, minnows, and silversides that provide food for striped bass, bluefish, weakfish, and other popular american sport fish. Atlantic croaker, another popular sport fish, uses marshes directly as nursery habitat. American eel and oyster toadfish both support small-scale commercial fisheries. (…)1

Valuable coastal fisheries, such as striped bass, bluefish, redfish, sea trout, flounder, skate, and catfish, as well as blue crabs, oysters, clams, and shrimp, are directly connected to the food web of both salt and freshwater marshes. As predators at the upper levels of the food chain, they become concentrators of the toxic substances found in these environments. They feed on bait fish, invertebrates, and mollusks that inhabit the contaminated sediments of many wetlands. In doing so, these important seafood sources accumulate carcinogens such as PFAS, mercury, PCBs, and other heavy metals.

Additionally, unhealthy marshlands harbor various new parasites and infections that significantly affect these prized fish, such as mycobacteriosis2.

As has been observed globally, the loss of these vital nurseries leads to a considerable decline in many of these predators, which in turn impacts the species that depend on them for food, including humans. This reduction creates severe imbalances in coastal and riverine ecosystems, often resulting in an overpopulation of parasitic creatures, further disrupting multiple links in the food chain.

However, this is only part of the story regarding wetlands.

Wetlands, much like the moors of Scotland and Ireland, the sands of the Sahara, the dark fissures of Iceland’s volcanoes, the fjords of Norway, the rugged islands of the Andaman Sea, and the peaks of the Himalayas and Alps, serve as a profound source of inspiration for artists and poets alike. Their gentle undulations and mysterious, tannin-stained waters evoke a wide range of emotions in humans, from irrational fear to deep reverence.

Wetlands are often the backdrop for many of humanity’s origin myths, as well as frightening tales of grotesque monsters and enduring faeries. They can stir hidden desires and memories of past lives, representing a world beyond death and the mythical purgatory found in various mythologies. Often seen as transitional spaces, wetlands bridge the realms of the living and the dead, the divine and the earthly, as well as the demons and the saints.

These enigmatic areas are frequently associated with mystery, sorrow, and hardship. They have long been considered inhospitable environments that only the fool, the mad, the witch, or the criminal dare to enter and survive. In this realm of “real unreality,” you may find sunken forests teeming with disease and despair, or, depending on your perspective, vast wonderlands filled with beauty and delight.